Alberta is mocked as Canada’s land of hicks and hydrocarbon heretics. But migration data since COVID tells another story: Canadians keep moving East of the Rockies.

For decades, Alberta has carried the caricature imposed on it by the national press and Ottawa’s political class. According to the story told in Toronto and Ottawa, Alberta is a backward land of book-banning conservatives, climate deniers, and angry rednecks clinging to hydrocarbons. This picture is painted with relish by columnists and cultural elites who see themselves as the custodians of Canada’s culture and virtue.

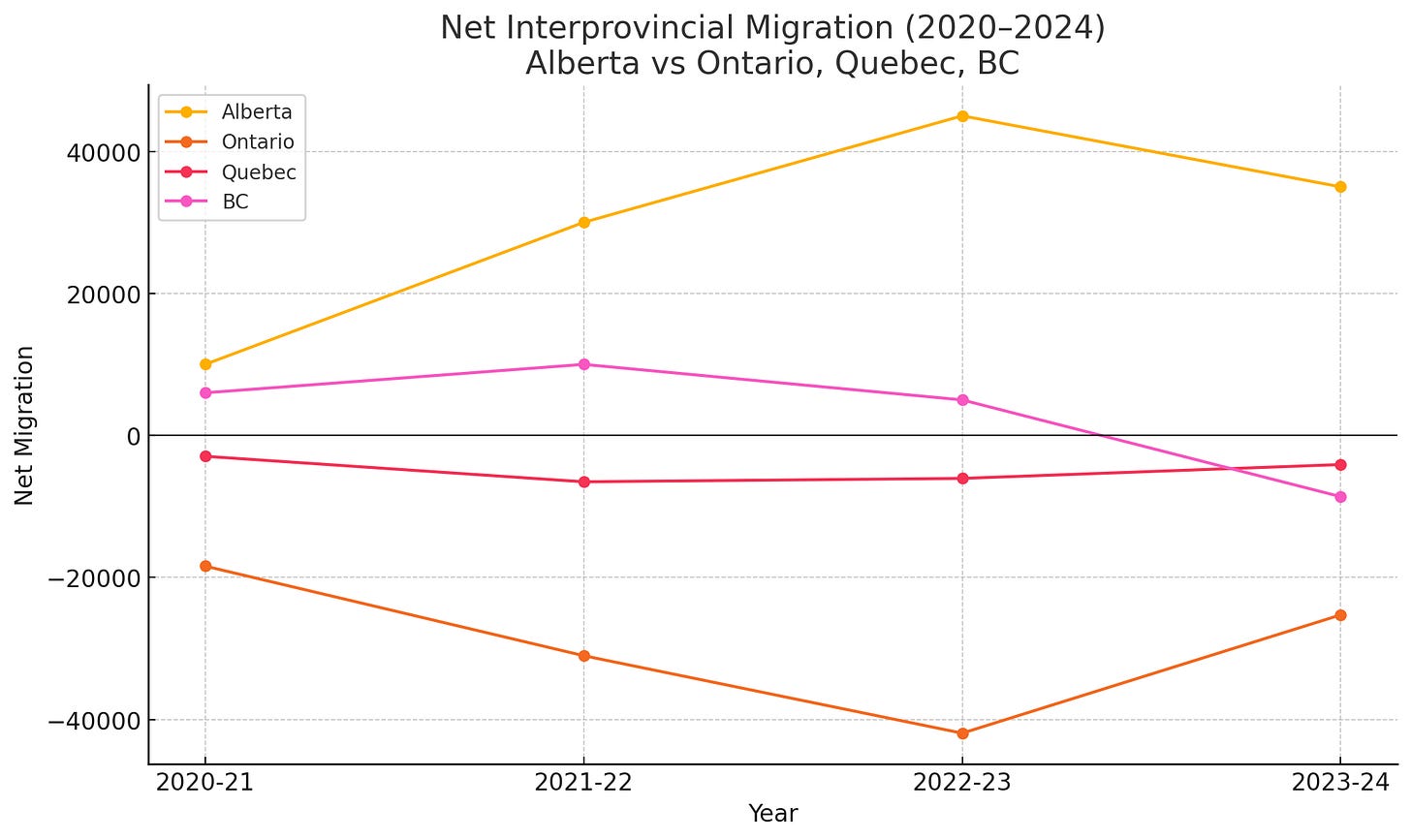

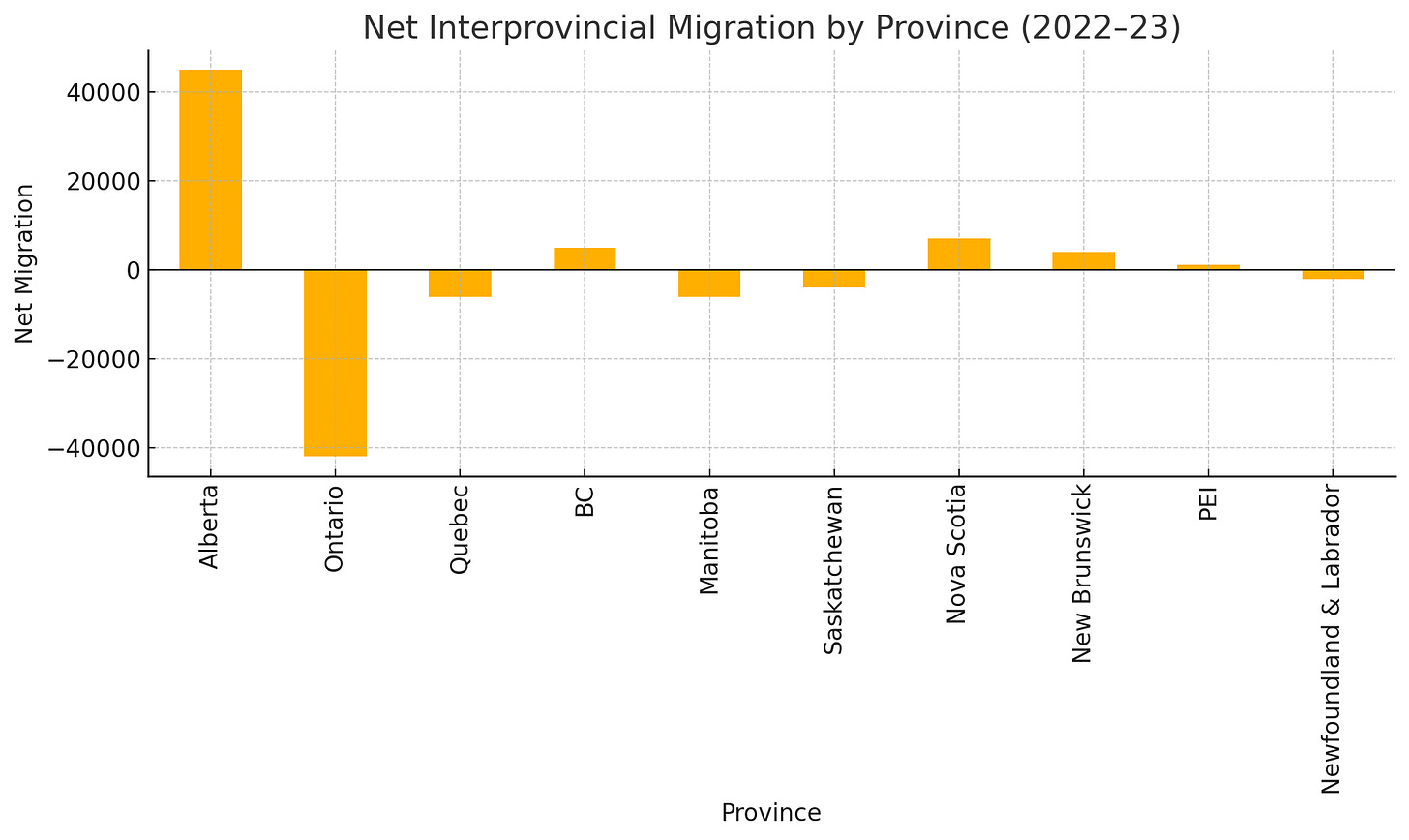

But numbers are stubborn things. And the statistical data on where Canadians are actually moving tells a story very different from the one Ottawa prefers. Migration flows since COVID show a decisive reordering of Canada’s demographic map, with Alberta clearly favoured.

Consider Ontario. Once the country’s economic engine, it has become the epicentre of outmigration. People want out. In 2019, Ontario was still attracting more people than it lost. By 2020, that had reversed. That year, over eighteen thousand more people left Ontario for other provinces than arrived. The following year, the number swelled to more than thirty-one thousand. By 2022–23, Ontario registered a net loss of nearly forty-two thousand—the largest in decades. The bleeding slowed somewhat in 2023–24, but the province still lost more than twenty-five thousand residents to other parts of Canada.

Toronto has been the centre of this flight. Between mid-2023 and mid-2024, the metropolitan region lost almost ten thousand people to other provinces. Far more damaging, nearly seventy thousand left the city for other parts of Ontario itself. This was not just an interprovincial story; it was an internal rebellion against unaffordability, congestion and crime.

British Columbia has followed a similar trajectory. For years, BC was a magnet. Its climate, its mountains, and the international allure of Vancouver helped it to attract more Canadians than it lost. But in 2023, the polarity of its magnetism inverted. For the first time since 2012, the province lost more residents to other provinces than it gained—more than eight thousand in net terms. Vancouver, the jewel of the West Coast, lost more than twenty thousand people in domestic migration between 2023 and 2024 alone, combining both interprovincial departures and moves to other parts of BC. Kelowna and Victoria, once celebrated as migration darlings, also swung into negative territory. Paradise has its price, and residents are increasingly unwilling to pay it.

Quebec’s story is less dramatic but no less telling. Year after year, the province records steady losses to other provinces, between three and six thousand annually since 2020. Montréal in particular has struggled. In the single year of 2020–21, the city shed forty-eight thousand people through internal migration. Even as that figure softened in subsequent years, Montréal continues to lose tens of thousands to other parts of Quebec or to other provinces entirely. For decades, Quebec has leaned on foreign immigration and relatively higher birth rates to offset these losses, but the persistent outflow of talent and families reveals a deeper malaise.

Haultain Research is a reader-supported publication. To continue reading, go to the Haultain Substack here.